June 2022 | An Interview with Alan Craxford— Jewellery Maker and Designer Extraordinaire

Part I: Not many contemporary artists have pieces in the permanent collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. Alan has two—a pair of niobium earrings and a pendant brooch. We will discover how the two pieces are linked. Our interview was conducted on Zoom.

Alan is just completing a book: In Search of the Blindingly Obvious. Alan explained, Part I of the book aims to encourage us to look at the world around us differently, for it is my contention that its Prescence is Blindingly Obvious if only we learned to look properly. In the Creative Process, like so many things, you have to get involved, and immersed, so that time disappears, and then it can begin to reveal itself. We all have a capacity for creativity, and if you look at life in a particular way it gives you everything you need to know.

Life is endlessly adaptable because it is a part of us. The book shows us many ways of working creatively and how people’s lives are changed as a consequence, bringing folks together more harmoniously. In other words, it connects to something both within and beyond ourselves.

Part II features my work mainly photographically because it should speak for itself and not need much explanation or interpretation The book is a gathering together of 40 to 50 years of working, and, most importantly, being committed to what I have been drawn to in life.

My teacher, Irena Tweedie, gave me very clear instructions of what I should do, some 40 years ago, “If you don’t want to meditate or pray you don’t have to. However, you must do your work… That’s what you’re here for. That’s what you must do. And You will see as you go on it will get better and better. For your work comes from the Higher Self, part of the Divine in you and you will be bringing that through into every piece you make. And you must be a success in the world—that is important.” (I feel this demonstrates clearly to those who can see how the Divine permeates all creativity, and thus helps manifest its presence in our world.)

At my request, Alan shared some of his life story. There used to be in the UK an “Eleven Plus” exam that determined at age ten or eleven your future education and prospects. I failed mine and could tell that my father was very disappointed. He was a talented pioneer in the plastic molding business in the 1950’s. He started a company that grew to employ two hundred workers. His first love was making the very complicated molds which have to split and come back together for the plastic to be injected into them under high pressure. Then this process is repeated in mass production. Like many men, my father could understand academic success but I’m not really academic—my way is to make things.

We were notified, out of the blue, that a new school, a tech high school, had been built by the County of Kent in the next town. I was accepted on interview at age eleven. Dane Court Tech High School was brand new. It had two large metalworking workshops, physics and chemistry labs, and a large art room. It was much more about doing things. I found I was good at making things and that I enjoyed it. My parents didn’t really understand or value that kind of gift.

At sixteen, I went to Art School and trained to be an industrial designer, which was a bit of a cop-out to please my parents. I was quite good at it but had no great joy or love for it. I worked for two large companies for five years.

I became very ill at 22 with glandular fever. It lasted two months and was awful. So, I had to go home to my parents. I was thrown back into myself. It is not something I would wish on anyone, being exhausting, one’s body full of aches and pain. It took over a year to get over it. However, the introversion it creates is profound and forceful.

It became clear that I couldn’t go back and continue what I was doing. I then met these people who knew this mysterious woman who was writing a book in Scotland, and it seemed the most natural thing in the world to join them.

Mrs. Tweedie returned from Scotland, and I was invited to have a cup of tea. The night before, I had a dream. A remarkable one, I had never dreamed in my life before. My art school was in Canterbury, Kent. Although a rather war-torn town, it still had Medieval, Georgian, and Regency parts.

“In my dream, Palace Street, Canterbury, has a huge high wall on one side, the retaining wall for the Archbishop’s Palace. I was sitting in the back of a Mark 9, Jaguar, two-tone blue. My mother is in the front beside my father. My father drove to the left curb, and I got out. The car was going back to the house, and I knew I wasn’t going with them. I took the first turning to the left. I walked through these terraces of Victorian houses. The road wriggled around a very neat and pristine landscape. A river meandered through a green sward and willow trees. As I walked along towards this bridge, I saw a pathway go off that led to this beautiful Queen Anne home in red brick. There were raised, large double doors at the front. I walked towards the house, pushed the doors and they opened. There was a perfectly square entrance hall, and the doors were replicated on each of the four walls. On the floor was black and white checkerboard style marble. I was overwhelmed by the beauty.

“I looked to my right. There was this great pair of doors. I opened them out towards me, and the space it revealed was very low. To get in, I’d have to go down on my hands and knees to squeeze through. I found myself in a room with an enormous bed and I knew there was someone sleeping there. The ceiling got higher and higher as I came further into the room. It was an enormously elaborate bed. I knelt on the floor and realized that in the bed was this extraordinary woman. And as I knelt, she rose out of the bed with her hands raised facing me and sat up. She had very long hair, and I saw that her hands and face were painted with designs, and she just looked at me.”

I started leaving my parents’ home with their big car, and had to find a way of getting through life. The design element stood out throughout the dream. I was fired from my job and was given enough back pay to keep me going for a while. I discovered, for the first time, what love was all about through close and intimate relationships, and a sense that there is something greater that also loves one.

So, I came to jewellery quite late. I had studied some of the elements of working with metal. Jewellery seemed a natural choice. There wasn’t much else I could do. I began to make things and occasionally even sell them.

I mopped floors, counted cars at road junctions, and did other strange jobs to get by. Eventually, when people saw my work, things began to change. I met people who asked me to make pieces for them. And then I applied to the Royal College of Art and I didn’t accept their offer to do jewellery and silversmithing, because my first choice was interior design. Clearly, they saw something I didn’t at the time.

|

|

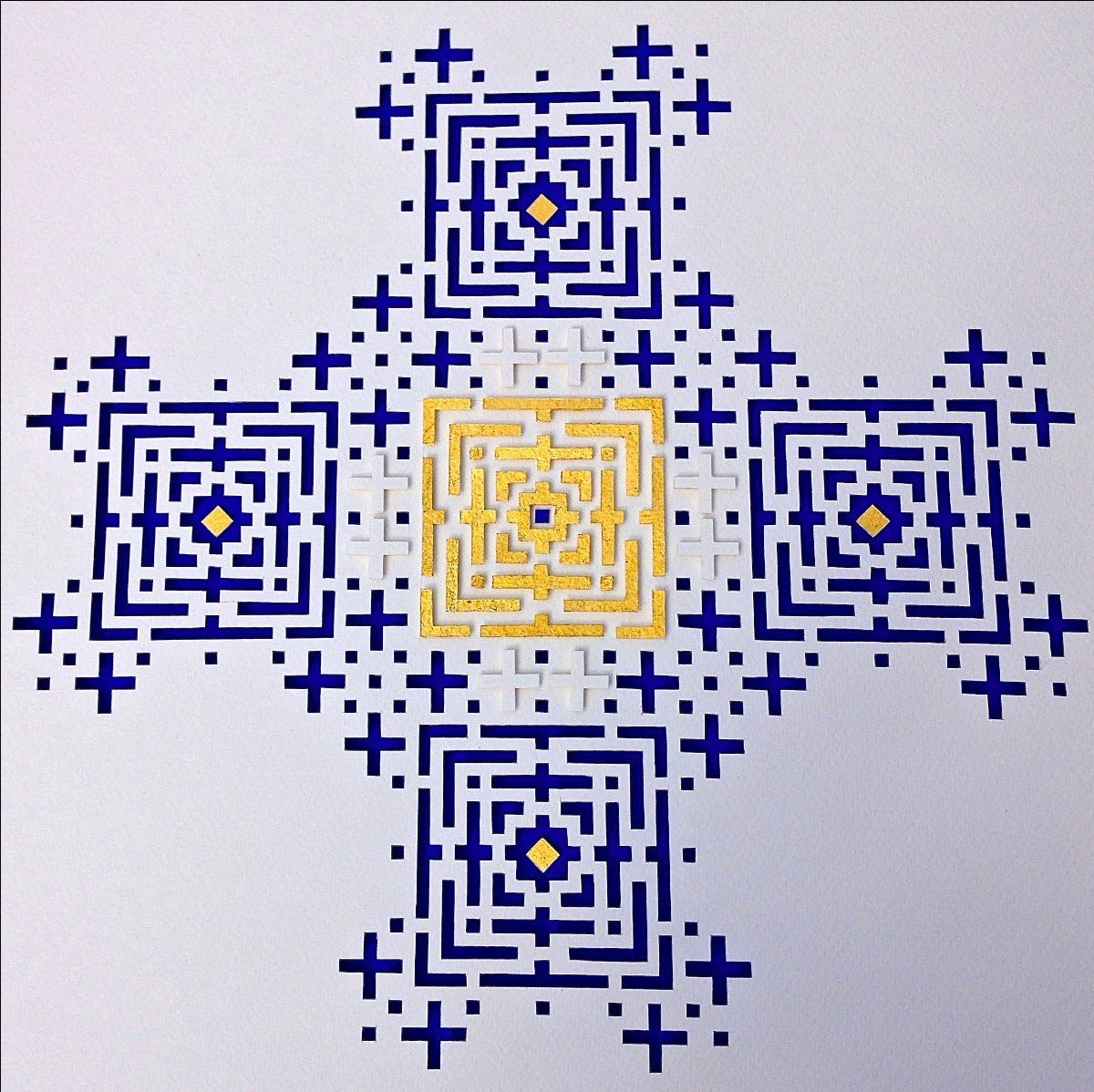

| Golden Thread Brooch. Photo by Simon B Armitt | |

| “The Golden Thread is sometimes visible and sometimes not – according to the light with which it is seen. However, it is always there and never leaves us.” | |

I was unemployed for a while before I found a part-time job teaching adults jewellery making. The one thing I can say is that I have no qualifications whatsoever in teaching. I learned it all on the job.

Teaching was a very valuable experience. It was quite fun and I stuck at it until I became a senior lecturer at University running first-year programs. I find it very grounding working with young people, helping them to develop a semblance of meaning in the work beyond the purely decorative. I have definite ideas about how to be a designer. I was a senior lecturer at Sir John Cass School of Art for twenty years and had taught there for ten years before that, and I also taught at Wimbledon School of Art.

The traditional way Sufis earned their living was often a mixture of things which left the person able to have enough time to pursue spiritual matters as well as pay the rent, look after family, and all one’s other duties. Because these two things are interdependent, they are both important.

I’ve been very fortunate that I fell into teaching as an occupation with no formal training. I got by with a combination of a bit of grace and an understanding that this is the way it’s always been. It’s the beauty of one’s home, paid for by one’s hands, that allows the jewellery and other things to happen. All the parts of one’s life interconnect. The container has both a physical and an alchemical or psychological reality. The act of creating it physically with real materials enables one to concurrently build inner containers.

There are several interwoven stories I will go into briefly as they are such good examples of the way my work seems to come about all by itself

Papercuts:

When you cut card or board with a very sharp scalpel blade, you get a very thin line, and so can cut a complex shape out of card. You get two things: the hole and its complementary left-over piece, which will fit exactly back into the space it came from. Any other way of separating materials, for example, with a saw blade, leaves a definite difference in the size of the hole and the piece left over, namely, the width of the saw blade. It’s worth thinking about the pros and cons of the two methods.

The Story of the Cross That Isn’t There.

It started because I had an exhibition of papercuts and photography at a local gallery. I said to the gallery owner, “I need some photographic enlargements of flatwork that I’ve done. Do you know anybody who can print them up?” He replied, “I do, and the bloke lives near you. His name is Aaron.” So I contacted Aaron and when we met, Aaron smiled, “Yeah, I can do the prints.” He was quite interested in what I did, and we got on well. I referred him to my website.

Next time I saw him to pick up the prints, Aaron inquired, “Do you mind if I ask you something?”

Alan: Of course!

Aaron: Do you ever make silver crosses?

Alan: Well, I made one once for a bishop.

Aaron: Oh, I was just interested.

Alan: Why do you want a silver cross?

Aaron: It’s to remind me of something.

Alan: Do you mind me asking what you want to be reminded of?

Aaron: Yes, it’s faith.

Alan: Why do you want to be reminded of faith?

Aaron: Because I don’t have any.

Alan: Oh, really! If I’ve got this right, you’d like something to remind you of something you haven’t got.

Aaron: Yes, that’s about the size of it.

Alan: Well, that’s one of the most interesting things I’ve heard in ages. I’ll go away and think about it

The thing about the paper cuts is that when you start with a square and cut them in halves, you get four squares and the flexible spaces in between. What do you look at first? The space in between or the four pieces?

I thought a cross made of nothing was really remarkable, and it was so unbelievably simple. So, when I went back to pick up some more prints, Aaron asked, “Have you thought about it?”

Alan: I have actually, and I showed him the little drawing

Aaron: I really like that, but I couldn’t afford it.

Alan: How much were you going to charge me for doing the prints? And he told me. That’s really funny because that’s about what I was going to charge for the piece.

So, we agreed no money needed to change hands and that we could explore the continued relationship between ‘nothing’ and ‘something.’

This demonstrates the power of nothing. What’s not there is as important as what is. We were both touched by what happened. Something in my life shifted radically, and it began for me a series of jewellery pieces.

Aaron’s completed piece was made from one sheet of silver. Each quadrant is textured and brushed in one direction. I then developed it in 2017 into a piece made of four parts set with four yellow diamonds. The geometric division of the space is left and right—above the arms of the cross is a square on each side, beneath the arms is another identical square on each side, and this is then repeated with one more square on each side. So, six in all plus the gaps in between.

Alan’s photos and video of the Pendant of the Hidden Worlds

The square brooch/pendant is made up of a series of layers. The back panel is highly polished facing up. The four top square panels are also highly polished, and gilded underneath, so that the two mirrors face each other. However, when you look straight on at the piece you cannot see the reflection (see the very first photo) which of course dances back to infinity. The four panels only reveal that secret when the piece is seen slightly to one side, which you can see in the photograph above, and in the short video. The four squares are not joined together, but they are cut from the same sheet, and then moved apart creating a space that is nothing! Thus, a cross is created from nothing, behind which is a reflection which goes to infinity. So, behind nothing is infinity. Four red stones are spinel’s set in 18-carat gold, and actually hold the whole thing together.

In both pieces in the Victoria and Albert Museum’s permanent collection, (see Alan’s green drop niobium earrings in Part II), something beautiful is created out of nothing but only when you have the information to look and to see, and so experience a reality rather different from what you might have presupposed.

You can enjoy Alan’s huge array of very fine pieces at AlanCraxford.com and watch his videos on Hand Engraving and Spinning Bowls (to be covered in Part II.)

UNSUNG SONGS

A thousand branches vault

into the bird-bound blue, while

feathered darkly on gnarly limbs

my unsung songs roost unseen.

I lean closer, closer

to hear them croon.

Loops of vibrant singing

sweep as bright-eyed robin

greets each branch and twig

before springing nimble.

Lilting notes propel

crocus shoots past snow

and rock. Somehow their bulbs

survive mole and worm.

Daffodils burst inside and

shining chime.

Love reels and spirals

to my roots― wills me keen

my sorrow, moan my pain,

woo those hymns snowed

under shame to take wing

in circling dance.

Receive the Earth-Love Newsletter, event invitations, and always a poem.