December 2019 | Part I – I used to say, “English is my second language, dance is my first.”

Leslie Davenport has been a professional dancer, an innovative therapist using guided imagery in a hospital setting, a founder of The Institute for Health and Healing, and currently, a pioneer in the field of climate change psychology.

I met Leslie Davenport at a memorial celebration for a dear friend of hers. Being an ordained interfaith minister, she conducted the Universal Worship Service that honors the world’s major religions, and held space for people to share their remembrances, both joyful and painful.

Would you first share some childhood experiences that, with hindsight, led you on your journey?

When I was six or seven, it was discovered that I couldn’t see very well. I wasn’t able to read the giant “E” on the top of the vision chart. I had no thoughts that there was anything wrong, since as children we automatically assume our experience is the same as everyone else. It turned out to be a gift. It helped me develop other ways of sensing the world because I had to find creative options to participate in the things my family and school friends were doing. For example, we read facial cues and postures with our eyes, and I needed to understand people and environments largely through other senses.

Other childhood teachers were my cats. I would study my cat as it became very still and looked up at the shelf it wanted to perch on. The cat’s focus was so concentrated on where it intended to land, that its gaze could practically draw the line of its trajectory through the air before it moved. Then it would appear to effortlessly launch and land. This childhood observation later influenced my guided imagery work by recognizing the value of intention and envisioning where you want to go: For example, envisioning a physical healing, a direction in life, the refinement of an art form, or a sports activity.

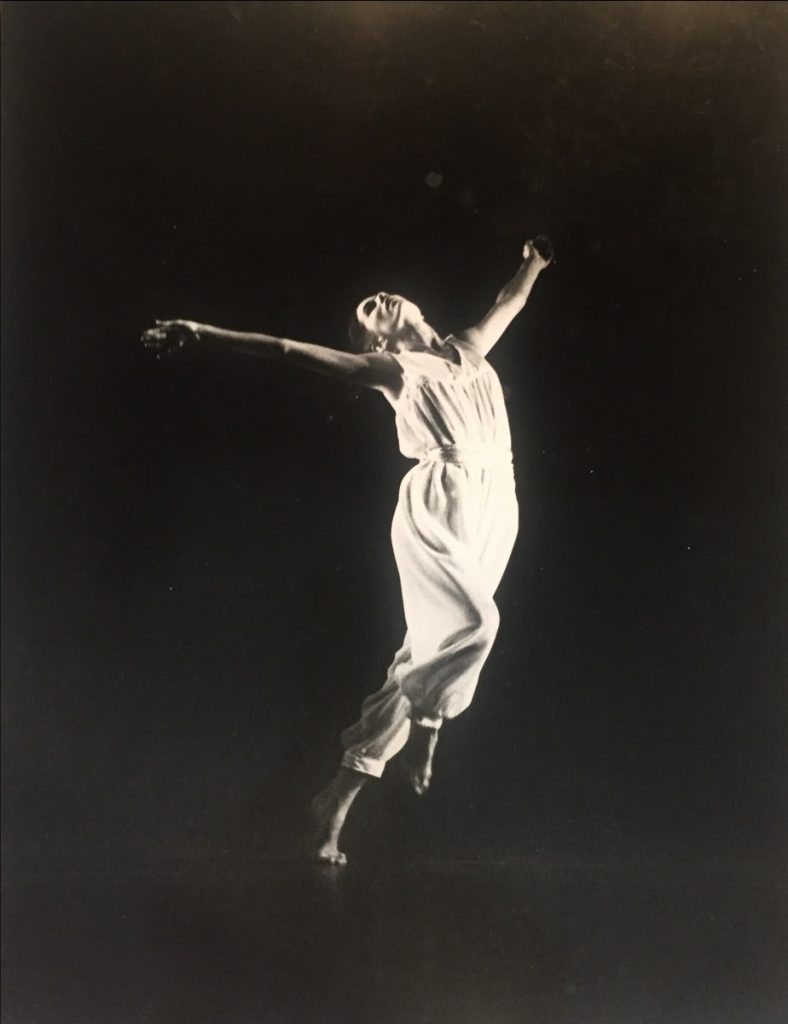

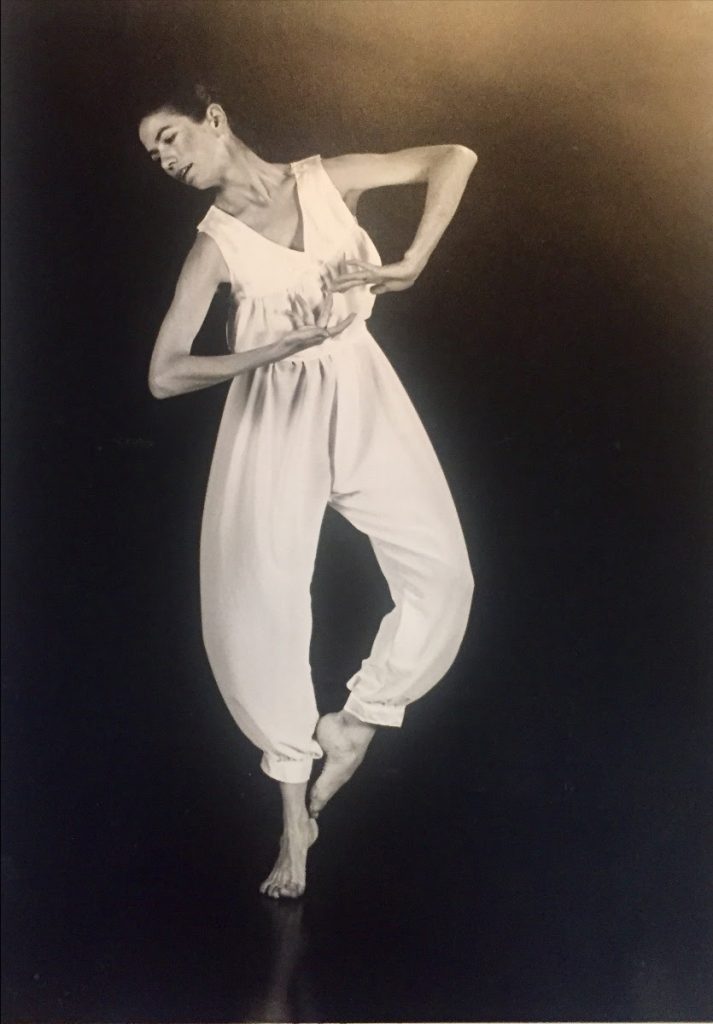

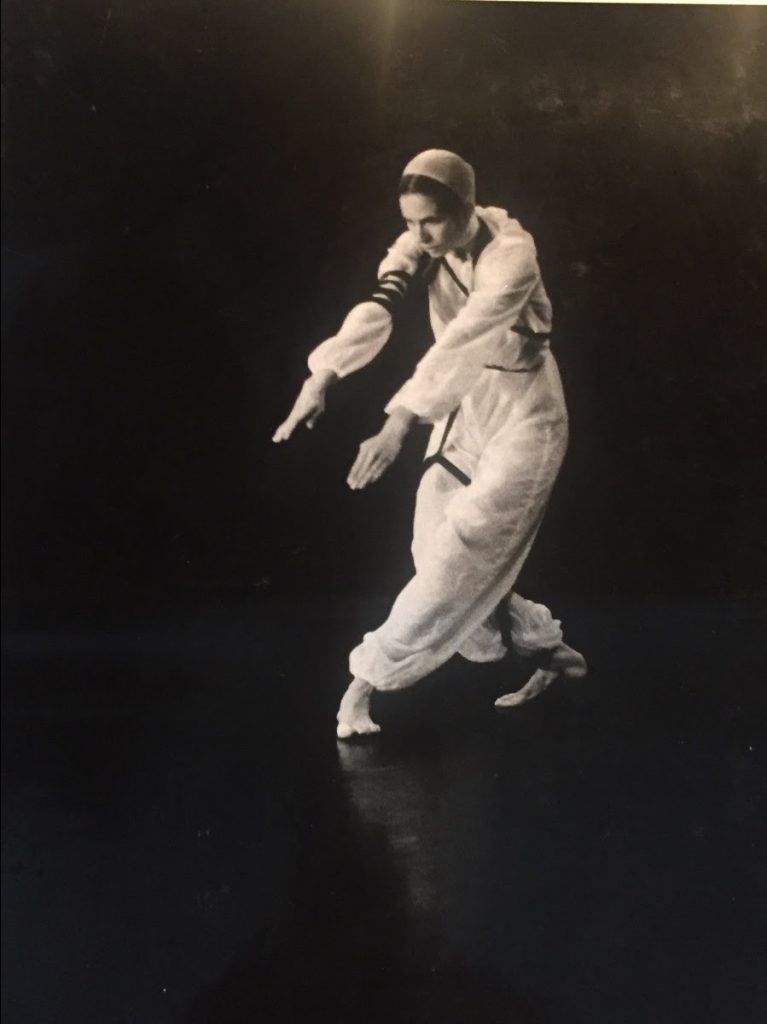

My creativity and sensing life kinesthetically led me to love expressive movement, especially modern dance. I used to say, “English is my second language, dance is my first,” because I could express so much more through movement. My connection to dance was a type of communication, potentially even communion, with the audience members in a non-verbal language that had the capacity to relate more than words ever could.

I was primarily performing and teaching dance through my twenties.

What drew you to become a therapist?

Several factors led to me not continuing with dance. One was having children; another was how challenging it was to make a living. I also noticed that most people who came to Modern Dance events were other modern dancers, and it was much too insular. My transition began when I changed from teaching dance for aspiring professional dancers, to teaching anyone who wanted to learn dance as a form of creative expression and self-discovery.

At the heart of all my career twists and turns is a fascination and deep curiosity about life and people: Why are we here? What is this place? From what source does wisdom arise? How are values formed? What is healing? While dance was a wonderful exploration into these kinds of questions, I felt poised at this point of change but wasn’t sure which new career direction to take. For about five years I held an internal inquiry: Where and how could I be of greatest service? So, I kept teaching dance, and waited.

One day I got a clear epiphany, “Other people are asking the same question. There will be people in many fields who aim to bring transformation and growth into the arts, medicine, science – all human endeavors — so pursue the field where your heart is naturally drawn.” I got the green light to start a degree in psychology—to further explore body, mind, spirit and emotions and how they come together. I had considered going to seminary, but the traditional ones were too constricting.

When I was dancing in my twenties, I saw a sign posted for Gurdjieff Temple Dancing. I attended that and, as a result, participated in a Gurdjieff study group for about five years, where I first heard the word ‘Sufi’. Then I saw a poster, “College of Spiritual Arts” with Allaudin Mathieu, Hamsa El Din, and Vasheest Davenport. I reached out to the group to teach dance, and after getting to know the community through that connection, Vasheest later became my husband and father of my sons. I studied the Universal Worship Service and became an ordained Sufi minister through the Ruhaniat.

Could you tell me about your work in guided imagery?

Dance taught me a lot about imagery. When I taught, I might say, “Let your arms have the quality of clouds, but let your legs move like lightning.” Those images elicited much more qualitative precision than describing the mechanics of the movement I was after. I wanted to deepen this understanding of the power of images.

When I was in an MS program in psychology at Dominican University, I wanted to connect psychological understanding to the body wisdom I had learned through dance, as well as spirit. I thought that working with health and illness, where these areas intersect so directly would be a rich learning ground, so I created an internship for myself in 1989 through the chaplain at Marin General Hospital.

A close friend had been hospitalized there with lymphoma and later passed away. I was in her room one day when the chaplain visited, and I was fascinated by the tender supportive role a chaplain could play. After my friend passed, I made an appointment and introduced myself, and told him I’d be back. Two years later, I asked the chaplain if I could serve as a Sufi minister in the hospital chaplaincy department while earning internship hours for my Marriage and Family Therapy license, and somewhat radically, the answer was yes!

I hadn’t done formal training with guided imagery but had experience of imagery in dance and Sufism. I asked permission to use guided imagery with patients and they gave me a one-year contract. About three quarters of the way through, I worked with a hospitalized woman who said, “The doctors and nurses here are great, but your work is really helping me heal. You are really humanizing medicine.” She added, “If you can convince the hospital to start a program to expand this imagery practice, I’ll make a gift of $300,000 to help you launch it.” So, with her assistance, I began the Humanities Program, later renamed the Institute for Health & Healing when we merged with a similar program at the California Pacific Medical Center in San Francisco. These efforts were the on frontier of what we now know as integrative medicine. It was prior to the Bill Moyers series Healing and the Mind, which helped usher holistic medicine into the mainstream. I hired an expressive art therapist and a massage therapist to work alongside the guided imagery I was providing and kept it completely free for patients. I brought healing art into the treatment rooms, and even a healing garden of botanicals into the cancer center’s foyer. When the money was spent, the cancer program hired me to continue the work.

Combined with the leadership of William Stewart, an ophthalmology surgeon and visionary, and many others over the years, the program grew to include many services. The bedside program expanded to a training internship that thrived for 17 years, bringing students from counselling psychology, massage, healing harp, expressive arts, and chaplaincy together to serve the unique needs of each patient. Currently there is an Integrative Medicine Clinic that brings together physicians on a team with nutritionists, acupuncturists, body workers, Feldenkrais workers, Ayurvedic medicine practitioners psychotherapists and mind-body eductaors to work in a collaborative way between themselves and with each patient. There are outstanding public lectures and classes. I was asked to write books on imagery, and there are now two that help make this powerful modality available to even more people.

I spent 25 years between Marin General Hospital and California Pacific Medical Center helping to develop the programs and services, teach and supervise students, and provide direct clinical care. The Institute continues to thrive today and has added additional sites in Santa Rosa and Sacramento.

Leslie explores her current work on climate change psychology.

Meeting Light

Through the windshield light gleams

on the fields, the light green willow leaves

running along the creeks

seem brighter set

against the just beginning greening hills

dotted with oaks, cows, sheep,

small clumps of shy-hoofed deer.

All chomp in well-manured pastures

as I, too, stand richly fed.

Vultures wing soundless circles overhead,

a perched hawk, red-tailed, its haunting

call withdrawn, spies smaller prey;

crows rush, gust and clatter

onto walnut limbs to cackle and muster.

I loom with the hunter,

quail with its prey, prattle

with companions until our souls

are full-flush-fleshed.

By Walker Creek, a thousand white woolen

eyes crown coyote brush,

dried fennel stalks drop silent seed

among these wild ones I flourish and breathe

under sun-fog-rain sway.

Coiling bends round the broadening bay

whose undulating ripples peep between,

lending ease and grace

against the pine-clad ridges, as the scudding sun

plays upon my skin into unseen depths.

Sprawled on the verge, a car-killed deer

awaits its airborne team with sharpened smell

to pick it clean. All seeps, sings and bounds in me.

Is it the light or the light

that I am soon to leave?

On boughed knees rest old trees sinking

into softened sod. The turn of seasons watch.

Their path is slowly set, while mine is filled

with urgency to laud and praise

give back one speck, one jot, of all

you pour into these marrowed bones.

Receive the Earth-Love Newsletter, event invitations, and always a poem.