July 2021 | Leslie Adkins’ Story: Part I – The evolution of an environmental scientist and a wool farmer with a no-kill ethic.

I grew up in the Washington, D.C. area and my family influenced me greatly. My father was an international health expert for the Peace Corps and the State Department and believed in trying to improve people’s lives by promoting access to education and family planning. He became Director of the first Peace Corps program in Brazil in the early Kennedy years, and we moved to Rio de Janeiro. My mother got her college degree as we grew up and then a master’s. She was a role model, especially for her two daughters. My mother was born in France and escaped with her American father and Anglo-Russian mother from Paris as the Nazis were entering in 1940. She was ten years old, and they moved to New York City.

I have three siblings and I’m close to all of them. We were placed in Brazilian schools in Rio de Janeiro, rather than the American School, and had to learn Portuguese “cold turkey.” I lived there between the ages of nine and twelve. It was tough, but great. I learned a lot—appreciation of differences in people, understanding diversity, and how much suffering there is in the world.

Once we came back to the Virginia suburbs of D.C., I had the opportunity to buy a pony with my saved allowance. I joined 4H and learned about livestock and caring for them. We also had a cat and a dog as a child. I trained the dog to do all kinds of tricks. I had a pet rabbit, and a great affinity for animals. I went to high school with government and CIA kids and a small black community who lived down the road. I worked for a vet in my last two years of high school and for one year after graduating. These experiences had a far-reaching effect on my ability to take on the whole sheep project. I have drawn on this experience in my current life because a shepherd must be competent in giving basic injections and administering veterinary treatments.

My parents moved to Paris during my last year of high school, and I stayed in Virginia with the family where my pony was housed. The mother, Sharon Francis, was head of the Lady Bird Johnson Beautification Program, and a strong conservationist. Thanks to her I became part of the effort to save an area along the Potomac River that was slated to become a luxury housing development. We succeeded, and it became a park. This was my first awakening to environmentalism.

My first degree was in the natural sciences. I was still thinking about possibly becoming a vet. My graduate work was a master’s in environmental sciences, where I was introduced to early scientific papers on climate change. Before grad school, I worked for a nonprofit developing methods for wetland restoration, and co-authored a paper in this pioneering field, which helped me get a scholarship. After I married, my husband went to law school, and I started with an environmental consulting firm in the D.C. area. My work at that time involved quantifying toxic exposure from the routine use of consumer items.

My research in graduate school examined the effect of storm surges and tides on the movement of marsh mammals in Assateague Island National Seashore off the coast of Maryland and Virginia. Just a few years ago my professor asked me for the raw data because of its foundational value to studying climate change in these Barrier Islands.

My husband and I had three children, after which I first worked part-time, and then not at all. Two of our children are adopted and we are a multi-racial family combining heritage from Europe, South America, and South Asia. Eventualy, I then worked for The Nature Conservancy, first as a volunteer and then part-time in a program with Latin American Partners that developed a geographic information system for mapping migratory grounds and routes for Neotropical birds in the Americas. That experience led to a two-year distance learning graduate program of study in ornithology. It was based in Australia and included two- field/lab trips in New South Wales. The ornithology studies enriched my later farming life, both as a no-kill “chicken herder” and by inspiring me to integrate wild bird habitats into the carbon farm plan at Heart Felt Fiber Farm.

We moved in 2003 to Berkeley, California. Alden, my husband, who was a regulator of securities, got a job with the now-extinct Pacific Stock Exchange to help them transition out of existence. We then were up for new challenges and adventure which took the form of purchasing an inn in Inverness. We ran the Inverness Valley Inn for seven years and made it eco-friendly with a farm, community garden, and solar energy. This was where I started learning more about fibers and their many uses. We sold the inn in 2013. That led us to move to a small farm close to Santa Rosa where I could focus on creating a model fiber farm that was eco-friendly, humane, and could produce beautiful handmade wool products. Since then I have learned everything I could about the animals, wool processing, grazing, carbon farming, and natural dyes.

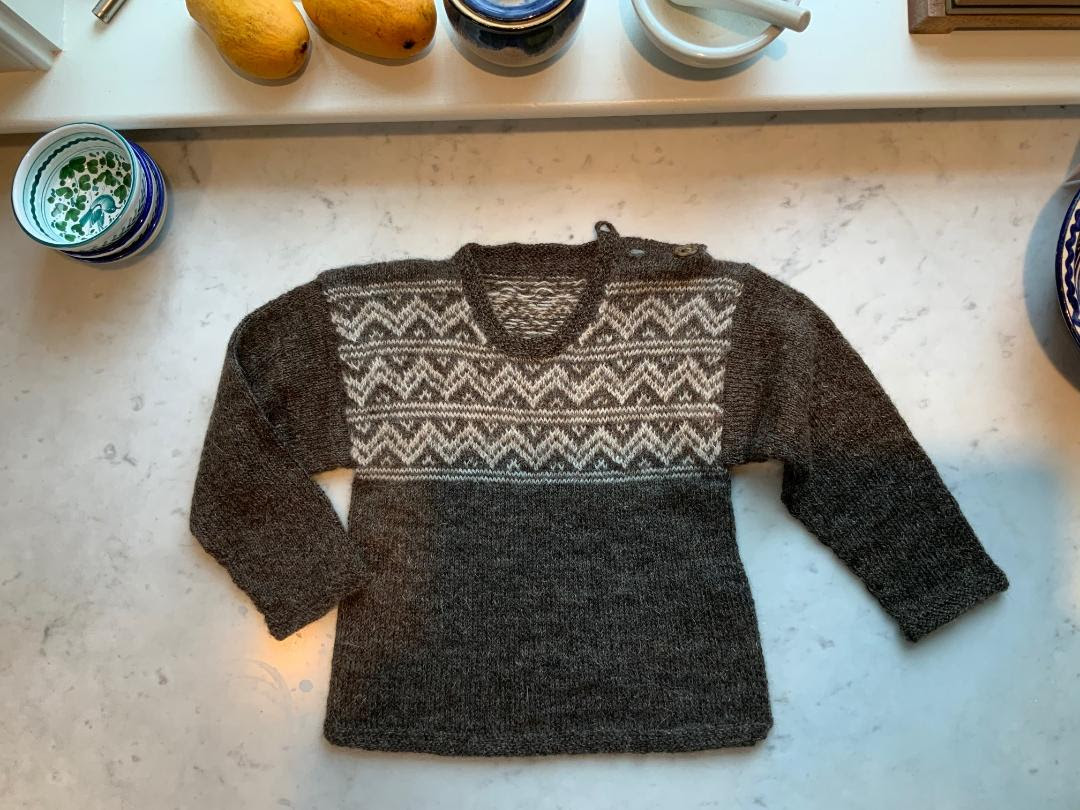

Long before we acquired the inn or the farm, I kept having these fantasy thoughts about having sheep and being a shepherd. I am convinced that some of us have a primordial “shepherd gene”…. The women in my maternal line knitted a lot and my father brought back hand-knitted textiles from a hundred different countries. During our time in Berkeley, I was introduced to the herd of grazing goats brought in annually to reduce the fire hazard, and became more fascinated by shepherding and managed grazing using portable electric fences. About a year into the inn, a guest who was a professor of chicken science at UC Davis, said, “You should have some chickens and sheep and share them with your guests.” The first two sheep were Icelandic that a local person was selling because they couldn’t take care of them. We found an Icelandic ram and had three lambs. They’re lovely old wethers named Casper (white wool,) Randy (white and chocolate, moort in Icelandic,) and Turi (milk chocolate.) (All of our herd have been named by my family.) They are now twelve years old, and I’ve just moved them to our new farm in Illinois. We moved because of climate change and the fires, which have affected my lungs badly, and also to be close to our daughter and grandchildren. Turi is totally blind and learned to find his way by following the others and paying attention. Next came two miniature dairy goats. It was educational for all the families who visited the inn.

We are a no-kill operation. All the boys are wethers (castrated), and get to lead their full lives in contrast to the norm, which is off to the butcher by six months. They give better and more wool than ewes because they don’t go through all the hormonal ups and downs. In traditional shepherding, ewes are made to have lambs every year until they can’t and then they are killed. Our operation is based on the “family planning” that my father advocated; ewes are only bred when there is room for their progeny to stay in the flock. The flock is a cohesive entity with long-term relationships and codependencies.

A friend told me about the rare, tiny Ouessant sheep, an ancient conservation breed from the Island of Ouessant off the coast of Brittany, France. We acquired our first two in Massachusetts and brought them to California in the back of a Prius. Over time I gained the trust of the breeders (who have created this new breed in North America by artificial insemination) and they allowed me to help a young shepherd bring some breeding sheep from Massachusetts. Together with a few others we now have the “Ouessant West” Collaborative Population to carefully maintain this rare line. Ouessant sheep have a number of unique characteristics. They are the smallest breed of sheep in the world which makes them particularly useful for eco-grazing, as they do not compact the soil. Unlike most sheep, they browse as well as graze, which makes them comparable to goats in clearing unwanted brushy vegetation. Black is the predominant color and the Ouessant black is uniquely intense due to more pigment than other black sheep. They are unusually intelligent; the French call them “The Charming Sheep.” They are long-stapled sheep with a very fine undercoat and a coarse, strong overcoat, and they produce more wool per pound of sheep than other breeds. Their wool is versatile, with many end uses because the fine undercoat can be separated from the strong outercoat for different textures.

The wild mouflon is the ancestor of all domestic sheep. Ouessant Sheep and related Northern European Short-Tailed primitive sheep retain more characteristics of the wild mouflon than more common “improved” sheep. There’s been an explosion of DNA studies on sheep, and they suggest that primitive sheep such as Soay, from the St. Kilda Archipelago off Scotland, and the Ouessant hail from the first wave of human migration to the region, and they comprise unique branches from the main genetic tree of all other sheep.

I thoroughly enjoy the whole learning experience from Wool to Wear and from Fleece to Shawl. The Ouessant wool has so much life in it. It’s so much fun to process by hand. I’m not a shearer but I’ve learned every other step in hand processing wool from raw wool to finished product… Now, much of my wool is processed at a mill because I do not have time to hand-process all of the wool produced by my sheep. The only way to know wool and get good at it is by starting with the raw wool, learning to skirt the wool, separating the parts that are good for different end uses with a little leftover for compost. Primitive sheep wool is low in lanolin, so you can spin and card with the raw wool. But normally you scour it with hot water and eco-biodegradable soap that removes most of the lanolin. Traditionally the Ouessant inhabitants would use the “suint method” for cleaning wool whereby they would collect rainwater in a tub and put the fleece in and let it soak for a week or more. Fermentation starts and the salts in the suint (sheep sweat) do a good job of cleaning the wool and removing dirt and some of the lanolin.

You then rinse the fleece with fresh water, and separate it out by hand, and put it on a screen — not in the sun, but in a breeze if possible. You don’t want to agitate the water because felting will naturally occur. The wool is now ready for carding, to align the fibers before spinning or felting. This can be done on a drum carder or hand carders (or even dog brushes.)

Felt was probably the first human-made fabric. People would find tufts of wool left by shedding wild mouflons and learned that if subjected to water and friction the individual fibers join together permanently. Each fiber has small barbs along it and felting causes the barbs to lock together permanently. Generations of humans have made basic items such as hats and boots from felt.

Felt is produced with hot water, friction, and soap or detergent. As an art and handcraft felting has evolved considerably in recent years. Machines like a felt roller and needle felting loom can help make rugs and larger works. In the last 10 to 15 years hand felting needles with barbs at the end have become available; repeatedly pricking the needles in and out of wool binds wool into dense strong fabric. We ended this part of the interview because Leslie needed to tend to one of the goats that had caught an infection while being transported from California to Illinois.

What makes Leslie’s farm different from most is her method of no-kill farming. Ever since I was a child, I’ve been very aware of the suffering of humans and animals, and it’s been very important to me to eliminate any suffering I can. There’s a small group of us in Northern California, the Tender Shepherds, who are figuring out a model for other shepherds to try non-suffering approaches.

I became a vegetarian about thirty years ago, long before I had a farm. Having an intimate life involving chickens, goats, sheep, and camelids has only strengthened my beliefs. I’m so aware of the life force of animals and their joy of living and their will to live. I’ve become more aware of the suffering of most farm animals because they are not valued in themselves but only as commodities. When their lives are cut short to turn into food it causes great distress for the other animals. Being put into trucks creates great anxiety among them. I’d much rather eat plant-based foods and, from an environmental point of view, the world is better off.

New Home

The Master Gardener and his love

have moved into my home.

I no longer recognize it.

My small rooms give way

to wild iris, cluster-lilies,

blue-eyed grass. Yellow

monkey flowers and

owl clover abound

in the living room. Walls

crumble, goats roam

the hillside. By night,

coyotes howl and romp.

What am I to do, now

that my prayer’s come true?

Receive the Earth-Love Newsletter, event invitations, and always a poem.