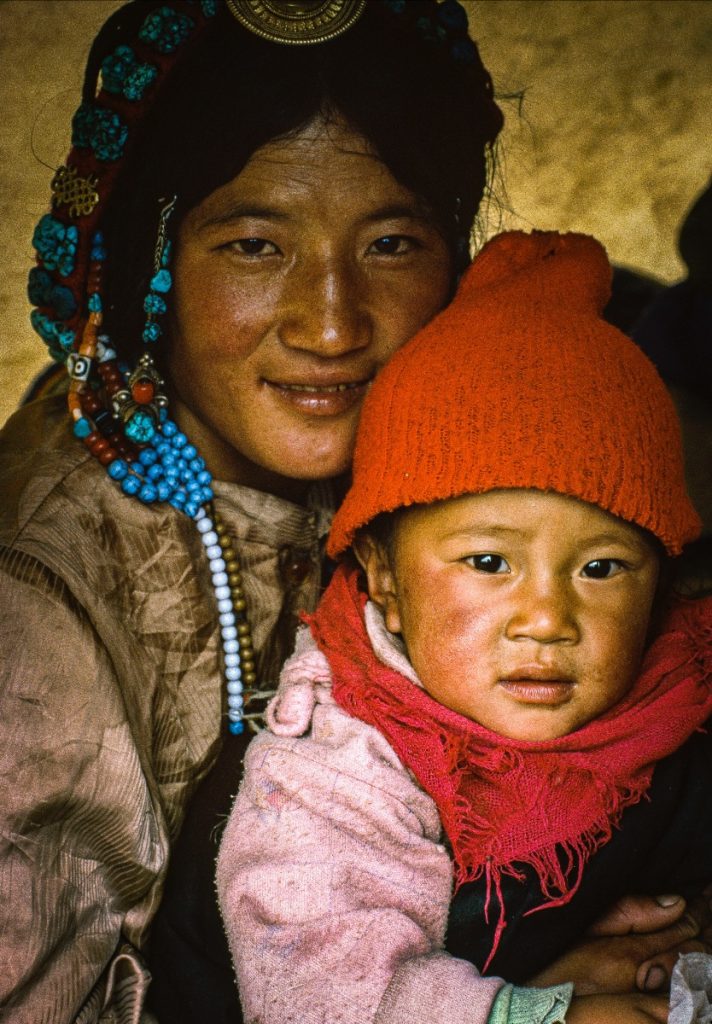

March 2023 | Interview with Diane Barker, Artist, Photographer, and Chronicler of Tibetans

Part II

In Part I, Diane described the Mamos Puja ceremony, its significance for the Earth, and how we can contribute our prayers and financial support to it. The Mamos Grand Puja is scheduled for June 2023, and ways to send money have been simplified to a “Donate” button on Diane’s website. (There are more details at the end of this interview.) Diane also related her story from painting mandalas to photographing Tibetan lamas and their communities. She ended with her first encounter with Tibetan nomads in Ladakh.

Later in autumn 2000, a trip visit to nomads in eastern Tibet came together via Chodrak, a Tibetan living in Austria who invited me to accompany him to his nomad family in Amdo. Hilary Hart, an American friend, came with me to these high-altitude grasslands in old eastern Tibet, now Gansu Province in western China. As an experienced trekker, she had all the right clothes and thankfully loaned me a jacket. Another friend loaned me a sleeping bag, and a third loaned me a small tent. On the very first day, we got to the village where Chodrak’s mum now lived and met his brother Choephel, a very laid-back guy. The next morning, we set off on horseback for Choephel’s nomad camp in the grasslands, accompanied by a group of his young nomad friends. It was raining and cold but I was so happy, I started singing. The guys started singing, too. Weirdly, I felt as if I’d waited my whole life to be in this place, on the move.

Hilary and I spent two weeks with Choephel, his warm and wonderful wife Yeshe, and their little girl, Dolma Kalsang. They were ebulliently friendly, good-natured, and amazing. We had been given a few Tibetan phrases by Chodrak which we never used—we communicated by miming and soon understood each other. Choephel was a master of mime as he had practiced on a brother who was both deaf and dumb. Hilary was particularly good at picking up local phrases and did a lot of the communicating—I was somehow quite shy, but by the end of the trip I had retained the local dialect word for raining – which literally translates as “sky falling down”—which it did a lot of in the time we were with the family.

Despite all the borrowed clothes, plus my own, I was freezing at night and cried with the cold at first. Yeshe took pity on me and gave me a home-spun yak wool blanket to put over my sleeping bag. I was better prepared on later trips!

We had one quick wash in a stream in the two weeks we were with the family. Our clothes were filthy, smelly, and crusted in mud. We both thought about throwing them away but decided to take them to the Chinese laundry in our hotel once back in Chengdu, and they came back as good as new!

Since then, I’ve spent mostly two or three days at a time with a nomad family. Some I have visited several times over the years—like Wangdrak Rinpoche’s brother and sister-in-law Rabten and Demtso, Yeshe Tsering and his wife Palmo, and Sonam Wangbo and his wife Pema. One of my favorite trips was the second one, in 2001, with Oga Thingo, who took me to her ancestral village and translated. She is the granddaughter of a tribal chieftain and comes from a highly revered lineage from which many great lamas have come. While travelling together people told her of all their local problems, but also shared lots of magical stories of seeing gods and protector deities, which she translated to me, and which I loved. This trip is described in Diane’s ‘Portraits of Tibet’ under “Travels with Oga: We spent a month travelling around Oga’s area on horseback nearly every day, meeting her friends and relations, me singing my way across the grasslands, Oga talking to local people and both of us attending horse festivals and celebrations to welcome the visit of Dzongsar Khyentse Rinpoche…”

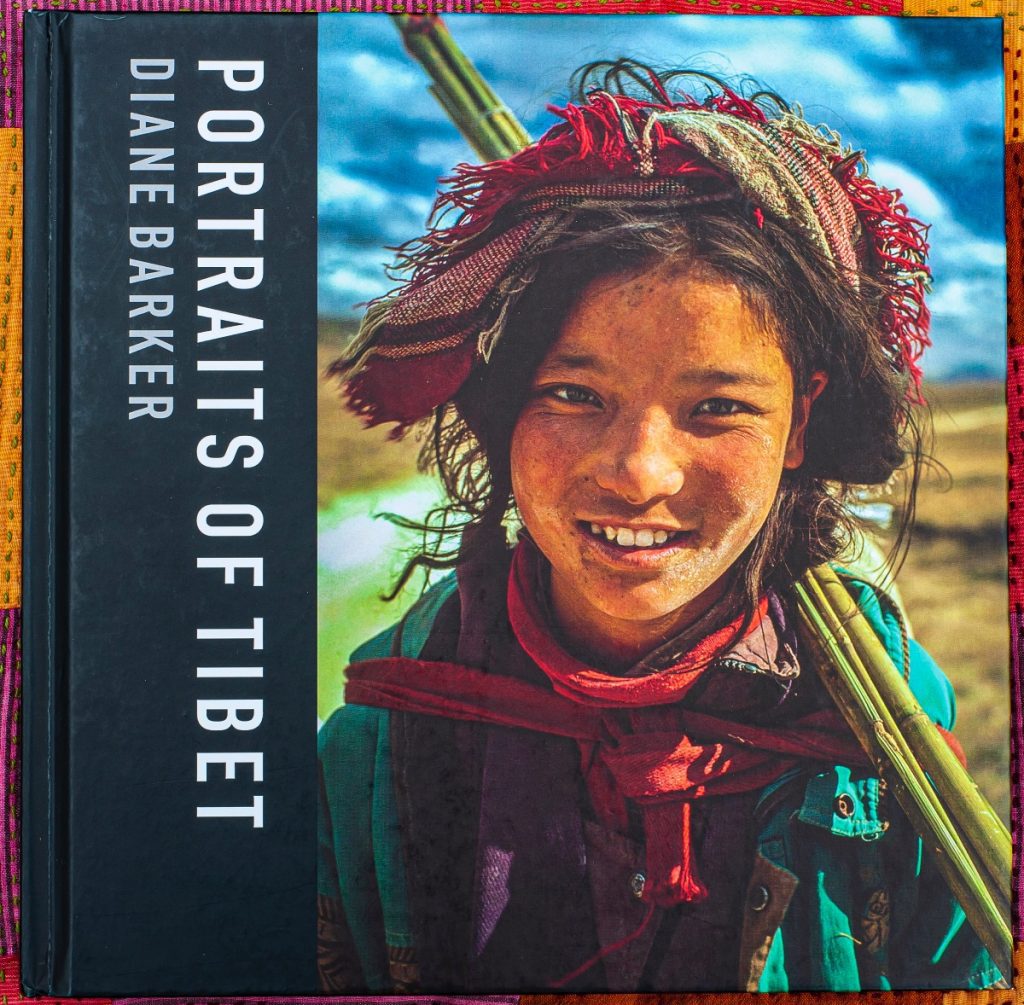

Portraits of Tibet

My wonderful publisher, Peter Gill, and I went through thousands of photos to begin to create a book about nomad life, and we both got quite exhausted at times. Peter kept saying: “There’s more than one book here!” He was particularly fond of the portraits, so I suggested that could be a second book—but somehow it came first.

The next book will explain nomad life much more: what they do every day; what happens when they move camp; the geomancy of where they set up camp; what they’ve seen—gods, goddesses, dragons; collecting caterpillar fungus or herbs to augment their income; the changes, such as new roads crossing the grasslands, cellphones, moving from a horse to a motorbike culture, watching TV inside a tent, and so on.

I realize that the main drive to create a book or books about the nomads is because their ancient, self-sustaining way of life as pastoralists seems threatened due to a lack of understanding and appreciation of their vital role as stewards of the high-altitude grasslands. When I returned to eastern Tibet in 2012, I became aware that a government policy (“resting grasslands”) of encouraging nomads into bleak resettlement villages had picked up speed. I was depressed and horrified by the emptiness of the land—there was no sign of the beautiful black tents and herds of Yak and dri* in two days of travelling into Kham from Chengdu. I was also aware that “settled” nomads were given no training in other skills, but were living on a kind of social security. In 2018, the Chinese government shifted its focus and suddenly affirmed that the nomads were good for the grasslands. Chinese environmental scientists had spoken. The nomads have now been told that they can take down the fencing that they had previously been told to put up, a government policy that led to overgrazing, and fights over access to water, among other things.

I would love to get one or other of the books I’m creating translated into Tibetan and Chinese and to give them free to nomad families. The Rinpoches I have come to know in eastern Tibet like the idea and have told me that the nomads would feel supported, seeing a Westerner chronicle their lifestyle as important.

Some nomads try settling and don’t like it, and want to go back to living nomad life. They have told me that they miss the space, the freedom, and the animals. At Heart of Asia, we help four families a year to either stay in nomad life or to return to it, although our main work is supporting a group of Tibetan children orphaned by the 2010 Yushu (Tibetan: Jyekundo) earthquake.

I asked Diane about the role of women nomads.

At most nomad camps I’ve been to, it’s the women who do a lot of the work. They milk the dri*, make cheese, butter, and yogurt, and also collect dung and spread it on the grass to dry as the fuel for nomad stoves. Traditionally the men used to have the role of protecting the camps and the herds of Yak, dri*, sheep, and goats from bandits, wolves, and snow leopards. They would ride around on their horses with guns ready. (Bandits were a real problem in eastern Tibet and were still around when I first went there. Some high Lamas used to say that the area produced “great bandits and great meditators”.) All the men’s guns and big knives have now been taken away by the local authorities which, along with government-imposed fencing, changed the men’s roles. These days the men help with a lot of tasks such as bringing the animals to the women for milking and driving the herd to pasture afterwards. They also go into local towns for some trading or selling of butter etc. Traditionally nomads conducted a barter economy with farmers in their area.

Nomad children have to go to school now, learning Chinese and English but barely any Tibetan, and boarding away from home, and that has changed things a great deal in many ways. For example, at Wangdrak Rinpoche’s brother’s camp, the men do the same tasks as the women, because so many of the children are at school or college and so there are fewer hands to help with all the tasks. Men, as well as women, also weave the yak wool panels which are stitched together to make the black tents, and they both make ropes—charu*—and slingshots, and build the clay stoves.

Many black tents have been replaced with white canvas ones, which are lighter to move around, and are often lined with cheap, Chinese fabric to make them warmer. I am told that the black tents work much better for cheese, butter, and yogurt making due to their particular ventilation qualities.

Sengko is very proud of his black tent with its traditional interior, and his beautiful clay stove made by his older friend Gyaltso. When a nomad family moves, they create a new clay stove in their new pastures. The old ones either biodegrade back into the earth or, if they are large, are restored and used again the following year. (If the nomads are left alone, their traditional lifestyle leaves a very light footprint.) Metal stoves are now supplanting the traditional clay ones because they are light and can be taken easily from place to place.

It’s the same with horses. When I first went to Tibet it was a horse culture—now the motorbike is ubiquitous. I’ve heard nomads say, “It’s easier to get around on a motorbike, and it’s cheaper than a good horse.” Some of them have both. There are many pastures, especially the high summer ones, that you can’t reach on a motorbike.

I do hope I can get one of the books I create into China, as well as elsewhere in the world. I hope my photography touches people’s hearts and inspires. It’s like a prayer or invocation—then the book gets out there and reaches whoever it is meant to reach. You never know who will be interested in it. You can’t judge, you can’t tell.

Yeshi Jampa, who comes from a nomad family in eastern Tibet, and who with his wife, Julie, runs a café in Oxford, “Taste Tibet,” wrote the most beautiful review:

https://graffeg.com/blogs/news/yeshi-jampa-on-portraits-of-tibet

The possible title for my next book could be Drokpa*—People of the Solitudes, or maybe People of the Black Tents. ******Dri: Yak is the male of the species. You would milk a dri

*Charu: the toggle on a cord, which attaches dri to a rope for milking

*Drokpa: the word Tibetans use for nomads, and was translated to me by Chodrak as “people of the solitudes, or high places.”

Please visit Diane Barker’s website to see more of her stunning photos and learn about her new book, Portraits of Tibet, including an outstanding book trailer set to a Tibetan nomad song. Portraits of Tibet is available internationally from bookdepository.com

We can contribute to the June 2023 Mamos”Grand” Puja ceremony with our prayers, and financially by going to Diane Barker’s website where she has created a Mamos Puja page with a “Donate” button that works for credit cards and Paypal. Thank you.

https://www.dianebarker.net/mamos.php

Her Unbroken Giving

I

It will happen unplanned,

like the gopher burrow

that diverts the waters

rushing down my hillside

from their appointed channels

to a flat patch―

where pools now gather, sit,

trickle through layers of

silt, sandstone, and clay

to the aquifer

that feeds the well.

II

When you were a child

and someone hurt you

did your petals close,

your shell snap shut,

did you burrow underground?

And what do you believe

will coax this wounded Earth

to show you Her face

in all weathers?

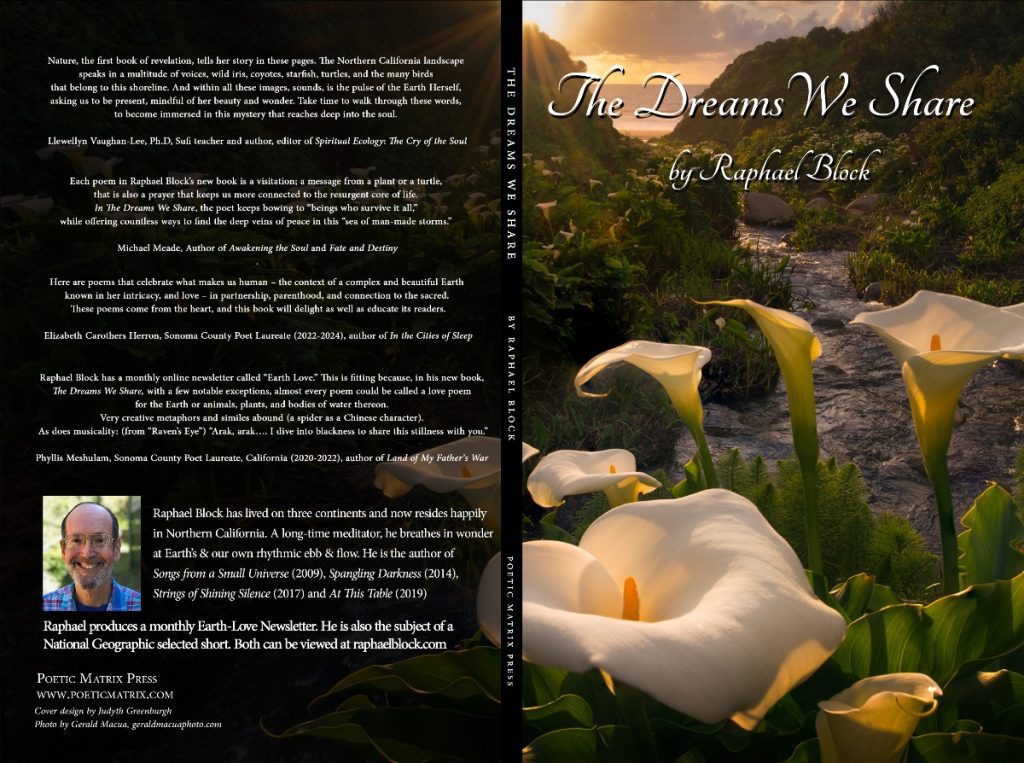

From my next book-to-be, The Dreams We Share

It was with excitement that two weeks ago, I launched an Indiegogo campaign for my new book-to-be, The Dreams We Share.

I turn to you, wherever you live, to support these poems born of love for this Earth and for life.

Please go to my Indiegogo at this link to watch the video that explains my campaign and the ways you can help in the next three weeks to make The Dreams We Share a reality.

With deep thanks,

Raphael

Please send me your inspirations of Earth-Love in photos, paintings, poems — whatever your passion so we can all be enriched!

I especially welcome the small and everyday, whatever you happen to notice that strikes a chord in you. Thank you!

Many thanks to Diana Badger for her careful editing and invaluable suggestions!

Receive the Earth-Love Newsletter, event invitations, and always a poem.